by Les Bengtson

The Colt .45 automatic pistol, and its copies, are one of the best self defense sidearms currently in production. It does, however, have several deficient areas brought about due to manufacturing short cuts and/or lack of adequate knowledge on the part of its producers. I will endeavor to explain what modifications I feel are necessary to produce to best defensive sidearm and why they are necessary.

The Basic Gun

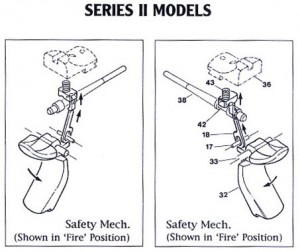

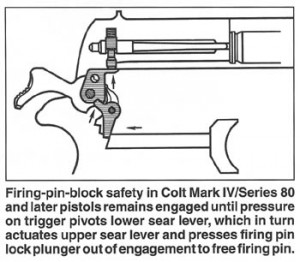

The best .45 autos are those of commercial Colt production. The Mk IV/Series 70 Government Model and the Combat Commander (pre Series 80) are especially fine weapons. The Series 80 guns, due to the firing pin safety block, are not as desirable for military use. They are more complex and difficult to maintain under field conditions. They do well as urban environment pistols. The fine Officer’s ACP is only available in this configuration.

Military surplus M1911 and 1911A1 pistols are excellent for back-up or spare guns. Quality is generally good although the finish may be somewhat rough. Some have seen extensive use while others have spent most of their time stored in arms rooms. The quality of the steel may not be as good as that of the Series 70/80 Colt. The slide is only “spot hardened”. This does not make them as suitable for extended use by private owners as the commercial Colts. When the military envisioned the weapons being used for an extensive number of rounds (match guns) they refitted the weapons with a “hard slide” of either Colt or other manufacture. These slides are marked NM followed by a contract specification number and are referred to as National Match slides. Some are available through surplus sales. The National Match slide is no better than a commercial Colt slide. For extended use, the military gun should have the slide replaced with either a commercial Colt or a NM slide. This normally raises the price to the point that it is equal to or above the price of a good used 70 Series.

Springfield Armory (Commercial production) guns are currently made to GI specifications in South America. They may be expected to perform as well as US made military .45s. Overall, the quality of the ones I have worked on has been adequate.

Other .45s. Various companies have produced direct or near copies of the M1911 and 1911A1 over the years. They vary in quality both among manufacturers and among production runs by the same manufacturer. Often, the guns require more work to bring them up to the same standards that a Colt can be brought to. Sometimes, even with extra effort, they fall somewhat short of what a good Colt can achieve. Work performed on non-Colts may be more expensive because of this. In the long run, you will have a gun that has cost as much as a Colt and may have lower resale value.

Recommended Modifications

Sights

You should have a good set of high visibility sights on a defensive arm. Adjustable sights are convenient for hunting, competition, or shooting a number of different types of ammunition. I have not found any yet that did not occasionally break, usually at the worst time possible. The Bomar seems to be the best of the lot. I do not recommend them if you only have one self defense pistol. If you have two pistols, adjustable sights on one of them allows it to be used for hunting and formal target shooting.

Fixed sights are much more rugged and stand up indefinitely on the defensive sidearm. The MMC fixed rear sight is a particular favorite of mine. The Novak sight is currently popular. It does not provide any better sight picture than the MMC, costs more and is more expensive to install.

All front sights should be silver soldered in place with high temp silver solder. I have never seen a silver soldered front sight, properly installed, that came loose. I have seen numerous front sights that were only staked in place shoot loose. The only advantage to staking the front sight is that it does not ruin the blue job on the slide. Since other gun modifications will probably require a complete refinishing anyway, have the sight soldered on and you will not have to worry about what to do when/if it breaks loose.

Trigger

There are two components to the trigger problem- length of trigger and weight and crispness of pull.

Trigger length is a function of the size of your hand and the length of your fingers. The pad of the trigger finger should be square on the front of the trigger or you will pull to one side. Try both the long and the short triggers. Choose the one that fits you best. Military triggers (M1911A1) have a rounded cross section at the front which seems to make the trigger pull seem heavier. They should be replaced with a commercial trigger.

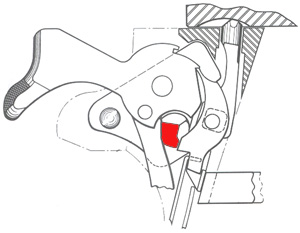

Weight of pull should be crisp and about 4 pounds. If your pistol has a crisp pull of 4-4 1/2 pounds you do not need a trigger job. If it does not, you do. Trigger pulls below 4 pounds should be avoided on a defensive gun, but may be desirable on a pistol used primarily for competition. After a trigger job, the slide should never be dropped using the slide stop. This jars the weapon and sometimes drops the hammer to half cock. When the slide is locked back and a new magazine inserted, cycle the slide as if it were in battery and this problem will not occur. Holding the trigger to the rear when dropping the slide from the locked open position has been recommended by some. It does work and may be required if you have not developed a strong grip on the pistol. I have found some students who have a problem with the hammer dropping to half cock on guns that do not do that for me. They did not grip the pistol as strongly as I do and the inertia of the slide going forward caused the trigger to jar the sear slighly, hence the hammer fell to half cock. Try it both ways. My way helps to develop a habit pattern that is used in certain malfunction drills taught in the modern technique of the pistol.

Beavertail or Ducktail Grip Safety

This modification spreads the recoil over a greater area and seems to lead to a better initial grip upon the weapon. Even a properly dehorned standard safety tends to damage the shooting hand when used for extensive practice sessions. Ross Siefried, former World Champion remarked, when he switched to a beavertail, that his hands never became hardened enough to avoid damage with the standard grip safety. The Clark, Wilson and King’s models allow the standard Government spur hammer to be bobbed and used with them. The Brown “high ride” safety requires that a Commander style cone hammer be used. The Brown is an excellent choice for the Officer’s ACP and similar pistols with shorter frames as it allows a higher grip on the pistol. Any of the listed beavertails will work well with the full sized frames.

Speed Safety

The extended safety provides a shelf to rest the thumb on when shooting. The standard safety is sometimes missed in practice. Mel Tappen wrote that a speed safety was cheap insurance against missing the safety when it was really needed. I concur. Additionally, the thumb safety is sometimes bumped into the on-safe position. This has happened at least once in a real life encounter. A speed safety, with the thumb kept on top of the safety when firing, will prevent this problem.

Ambi safeties are available for left handed shooters. They serve little use on a duty pistol for a right handed shooter. The concept that it allows you to use the pistol with the weak hand if you have been shot in the right arm has developed out of IPSC shooting. If you have been shot with the pistol in your hand, the safety is already off. If you are shot with a holstered pistol, you seek cover or attempt to withdraw. The right side safety can be released fairly easily with the index finger of the left hand by anyone who has practiced a few times. We recommend only the strong side safety except for strictly competition pistols.

Throating

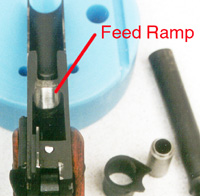

Most barrels, except the 70 and 80 Series Government models require throating and matching of the feed ramp to the barrel for any ammunition except hardball. Most of the 70 and 80 Series guns are roughly throated and may hang up with certain types of ammunition. Throating of the barrel and polishing of the feed ramp in the frame are cheap insurance against failure to feed. Lower and teardrop ejection port

Government models normally have a smaller ejection port than Gold Cups and Commanders. Enlarging the ejection port makes them slightly more reliable. Even on pistols that have the lowered ejection port, we open up the port slightly more for increased reliability. This is a small, but important, point.

Teardropping the ejector port is easier on the brass since the slide hits the case before it clears the ejection port and this modification breaks the sharp angle there. While I had previously believed that this is mainly a modification for reloaders, there seems to be some small, but definite, reliability increase with this modification. The slide strikes the cartridge lower on the brass and lessens the possibility of a “smoke stack” malfunction.

Stipple or Checker the Forestrap

Stippling or checkering the forestrap gives a firmer grip than the normal bare frame. Since the main force of the strong hand on the weapon is on the fore and back straps, this translates to a more secure grip on the weapon. This is particularly true on a weapon with a nickel finish.

Checkering looks very pretty and provides a very secure hold. Either 20 or 30 lines per inch may be used. It is acceptable for use in a duty holster. When used in a holster that is inside the pants or close to the body, it tends to abrade the clothing and catch on things. When used concealed, it tends to tear up the jacket lining. It acts as a very sharp file. It can make the concealed draw much more difficult due to this. It is also much more expensive than stippling.

Stippling provides a less abrasive surface than checkering. It is superior in every way to checkering on a normal duty gun.

Finishes

After having your defensive pistol modified, you should shoot the weapon until you are sure that it is set up exactly as you want it and that it functions with complete reliability. Normally, a reblue at the time of the modification is in order. While the bluing only provides marginal protection against rusting, it is often adequate for most shooters. It is also easily removed if you decide you want to make some change in the weapon set up. When you are sure that you have your pistol set up exactly as you want it and you have analyzed your carry pattern (in a belt holster, an inside the pants holster or a gun case, etc.) you are at the point to decide whether you wish to replace the bluing with a more durable (and more expensive) finish. For most people, however, a matte finish blue will be more than sufficient for the majority of their shooting and carrying needs. If you should decide you wish a more durable finish, there are several to choose from. Parkerizing, electroless nickel, hard chrome and TAF-1 (a molibdinum disulfide finish) are available. All are applied finishes that go on the surface of the metal rather than changing the surface as bluing does. They all have better rust resistance than bluing. The TAF-1 finish can also be applied to stainless steel providing both increased rust resistance and do away with the problem of a shiny pistol reflecting light. All applied finishes will wear over time and can allow rusting to take place. Removal of some applied finishes (hard chrome, electro and electroless nickel) require special stripping procedures. TAF-1 and parkerizing can be removed by normal refinishing methods.

Other Modifications

To be based upon personal preference and perceived need.

Funnel magazine well

This makes it somewhat easier to insert a magazine during a speed load or when loading with eyes on the target. Many people, by practicing more, do fine without it. Magazine funnels that bolt on to the bottom of the frame or the S-A Mag funnel/main spring housing should all be custom fitted to the frame. They are not perfect drop ins.

Match barrel bushing

This can provide a slight increase in accuracy. It is generally a part of work done on the more advanced guns. It is not strictly necessary on a self defense pistol. Any pistol having the 70 Series collet bushing should have it replace with either a match or other solid bushing to prevent breakage of the collet fingers.

Recoil Spring Guide

This system is unnecessary on the Government and Commander models and interferes with the proper “pinch check” of the weapon. The Officer’s ACP and some Springfield models have a recoil spring plug that is held in the slide by a small teat rather than the barrel bushing. These break, normally at the worst possible time, rendering the pistol inoperative. They should be replaced. In the case of these pistols, with their more marginal functioning, a full length guide rod and replacement plug is a must. Wilson makes the best system for both the Colt and Springfield pistols.

General

A general smoothing up of the moving parts in the action and “dehorning” (smoothing of all sharp edges) should be a part of any combat tune-up. Other items such as extractor tuning are done on an as required basis. A slightly heavier than normal recoil spring (18 1/2 # for the GM and 20# for the Commander) provide a little extra power when chambering a round. I use them on mine, but did not for many years with no great difference in reliability. Like the speed safety, it is a small bit of extra insurance.

The foregoing is a general guide to the combat modification of the Colt .45 auto. The suggestions are based upon extensive use of this weapon in the military, combat competition and practical instruction. I hope these thoughts will be of use to you in setting up your own self defense piece. Please feel free to contact me if you have any questions.

THIS MONOGRAPH MAY BE REPRODUCED ONLY FOR NON-COMMERICAL USE WITHOUT OTHER PERMISSION OF THE AUTHOR. REPRODUCTION FOR COMMERCIAL USE ONLY BY WRITTEN PERMISSION.

Copyright 1986, 92, 93, 96, 97, 98 by Les Bengtson

L. Bengtson Arms Company

Mesa, Arizona

(480) 981-6375

[email protected]

AAS, Gunsmithing

Certified Police Armorer

Certified Gunsmithing Instructor