by Jeff Lesemann

John Moses Browning (1855-1926) was born and raised with an arms making heritage. His father, Jonathan, had been born among the sparsely settled Tennessee hills, northeast of Nashville, in 1805. In those early days the flintlock rifles, fowling pieces, and pistols of the era were among the basic tools of daily life, necessary for self defense and hunting. Jonathan took a strong interest in guns at an early age, attracted by their mechanisms and construction, rather than by their utility. While he was still in his teens, he apprenticed himself to a blacksmith near his family’s homestead, in order that he might learn the gunsmith’s craft. Later, he made his way to Nashville, where he worked at the shop of an established gunmaker until his own skills were fully developed. In 1824, while he was still only nineteen years old, Jonathan completed his apprenticeship by making his own fine flintlock rifle. He then set up shop in Sumner County, Tennessee, married, and settled down to his life’s work and the raising of a family.

Jonathan Browning was not destined, however, to remain in Tennessee. In 1834 he loaded his family and their belongings onto wagons and set out on a four hundred mile trek to Quincy, Illinois, a new and fast growing town on the Mississippi River, squarely in the path of westward migration. It was here, during the next eight years, that two elements came together in Jonathan s life, with results that would shape the destiny of his yet unborn son, John M. Browning.

The first of these elements was a rifle which Jonathan invented and built in his Quincy shop. Percussion cap ignition had been invented just a few years earlier, and it quickly swept the flintlock aside. The cap was far more reliable than the flintlock, and it opened new possibilities for further developments, such as repeating arms. Jonathan exploited this potential by inventing a truly elegant repeating rifle. It was a .45 caliber underhammer design, with a horizontal opening cut through the receiver. The magazine was a simple steel block, made to fit into the opening. It was bored with five or more chambers, which could be preloaded with powder and ball. At the base of each chamber, a snug nipple held the primer cap. The block was placed in the rifle, and each charge could be locked into position by means of a simple lever mounted on the side of the weapon. As each round was fired, the shooter would unlock the block and move it into position for the next shot. Although the rifle had flaws, such as poor horizontal balance, the possibility of losing the primer caps, and the necessity of handling the hot magazine manually, it was a remarkable gun for its time.

The second factor that was to shape the remainder of Jonathan Browning’s life was part of a much larger turn of events, over which he had little control. Joseph Smith had founded a new religious sect, called the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, otherwise known as Mormons. Their theology was based on a series of prophesies, which, according to Smith, had come to him in visions. The zeal of Smith’s followers was to intense that the Mormon Church was the fastest growing religious group in the United States, but there had also been serious problems. Some of Smith’s teachings were viewed with scorn by more orthodox society, and the Mormons aggravated the uneasiness of outsiders by adopting a clannish and isolated lifestyle. This led to suspicions and to several incidents of persecution and violence against Smith and his Mormon followers.

In response to these difficulties, the Mormons embarked upon a mass migration, in search of a homeland where they could practice their beliefs freely. In 1839 they established a settlement in Illinois, a little more than forty miles north of Quincy. They named their new town Nauvoo, and it quickly became a model Mormon community, from which they reached out in search of still more converts. One of these converts was Jonathan Browning.

In 1842 Jonathan moved to Nauvoo, where he again set up his gunsmith’s shop. Just a few years later, however, he and his family were swept up in the great Mormon exodus. Joseph Smith 5 was set upon and killed by a mob in 1846, and Brigham Young, one of Smith’s more ardent followers, decided that he would lead the faithful westward, in search of a safe haven. In 1847 the Mormons moved to Kanesville, Iowa, which is now the city of Council Bluffs. There Jonathan once more set up shop, remaining for five years, while the main body of Mormons moved on to Salt Lake, Utah. It was Jonathan’s task to furnish as many of his rifles as possible for the Mormon settlers. Finally, in 1852, he joined the migration and settled in the town of Ogden, Utah. In 1854 Jonathan married the second of this three wives, polygamy being an accepted Mormon practice at the time. On January 23, 1855, John M. Browning, the first child of this second marriage, was born.

Jonathan did not continue to manufacture guns after the move to Utah, but he did continue his work as a gunsmith. At an early age John became a pupil and helper in the shop, to such an extent that he would later refer to the gunsmithing shop as his only real school. Although John Browning’s apprenticeship was just a natural part of growing up around his father’s shop, he learned so well that the career which followed caused him to be recognized, world-wide, as the most prolific and successful genius in the history of firearms.

In 1878, while Jonathan was still alive to see his son’s talent blossom, John invented his first gun, a sturdy, single-shot, falling breech rifle, which was to become the Winchester Model 1885. He then went on to invent the famous Winchester Model 1886 lever action rifle, and a host of other guns, including all of Winchester’s subsequent lever action and pump action rifles and shotguns. When Winchester balked at accepting John Browning’s design for a semi-automatic shotgun, he sold the weapon to Remington, and went right on inventing! He next turned his attention to the development of one of the first successful automatic machine guns, and it was from this work that his greatest legacy emerged, in the form of the modem self loading pistol. All of Colt’s automatic pistols have been based on John Browning’s patents, and, of these, the Colt “Government Model” .45 caliber pistol has become the most widely built and used, high power, auto loading pistol of all time.

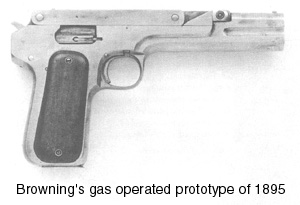

John Browning became interested in automatic and self loading weapons when he realized that much of the energy produced by the detonation of a cartridge was wasted. His first experiments aimed at harnessing this energy were focused on the gas pressure which built up behind the bullet. By tapping the gas pressure near the muzzle, and using it to operate an actuating lever, Browning succeeded in developing the gas operated machine gun. His gun was built by Colt, and later, under license, by Marlin, as the Model 1895 Machine Gun. It won acceptance by both the Army and the Navy, as well as by several foreign customers. Although machine guns and pistols may not seem to have much in common, Browning’s self loading pistols were, in fact, direct results of his work on the machine gun. Browning added a simple spring loaded disconnector device to the trigger mechanism in order to achieve interrupted, or semi-automatic fire, and it was this device which made semi-automatic pistols, rifles and shotguns possible.

Parallel developments of a similar nature had been taking place in Europe, and the early auto loading pistols designed by such pioneers as Bayard, Bergmann, Borchardt, Mauser and Schwarzlose were at least functional, though terribly complicated and unwieldy. In contrast, Browning’s first auto loading pistol was a gas operated, toggle action design which introduced the smooth and graceful lines that became common to all of his later models. The pistol made use of a detachable box magazine, housed in the grip frame, which also contained the firing mechanism. The mechanism was connected to the trigger by means of a cleverly designed link, which was wrapped neatly around the magazine. Compared to the early European pistols, Browning’s prototype was simple, compact, and highly reliable.

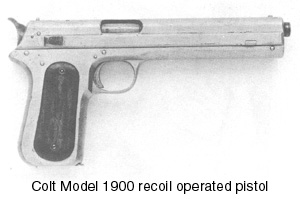

Good as this first pistol was, however, it was never placed into production. John Browning had no sooner completed fabrication of the prototype when he surpassed it with two entirely different designs! The first was a small pistol, in .32 caliber, with a blowback action. It became the prototype for the FN Model 1900 and the Colt Model 1903 pistols. This was quickly followed by a recoil operated pistol in the same caliber (.38 Colt Automatic) as the gas operated prototype. (see fig. 3). It was to become the Colt Model 1900, and it was gradually improved and modified until the Model 1911 emerged in final form.

Browning concluded that a recoil operated pistol would provide the most satisfactory means of locking the breech during firing, without the necessity of providing complicated linking and actuating mechanisms. A locked breech was absolutely mandatory in order to safely use high power ammunition, and Browning’s method of accomplishing a secure lock was so simple and effective that it has been used almost universally ever since.

The major components of the Model 1900 pistol consisted of the barrel, the slide, the magazine and the frame. The barrel was attached to the frame by means of pins which passed through pivoting links, located beneath the muzzle and the breach. The slide was fitted into channels in the frame, and with the action closed it covered the barrel almost to the muzzle. Corresponding ridges and grooves were machined into the top of the barrel at the chamber, and on the inside of the slide. With the action closed, the grooves would interlock and the firing pin housing closed off the chamber, completing the lock-up.

Upon firing, recoil forced the slide and barrel to travel rearward together for a distance of about one quarter of an inch. The links caused the barrel to pivot downward at the same time, in an action similar to that of a draftsman’s parallel ruler, until the slide and barrel were freed from the locking grooves. The slide then continued rearward to full recoil, extracting and ejecting the spent cartridge case and cocking the hammer. With the slide at full travel and the recoil spring fully compressed, the spring then took over, pushing the slide closed again as it stripped a fresh cartridge from the magazine and loaded it into the chamber.

The Model 1900 pistol worked quite well, and it was soon placed into commercial production. A small number of pistols were also sent to the Army for trials, but initial reaction to this new weapon was negative. The Infantry, Artillery and Cavalry all had their own ideas about the desired qualities of a side arm, and all three branches shared a deep-rooted preference for revolvers. Among the more valid objections raised by the first trials of the Model 1900 pistol were complaints about unreliable operation, the necessity for two hand operation during loading and cocking, and the lack of safety features. These problems would be corrected, one by one, as Colt and Browning worked together to refine the pistol.

In 1902 Browning added a slide stop to the pistol, so that the action would be held open after the last cartridge had been fired. Other changes included deletion of the early safety, a lengthened grip frame, with a corresponding increase in magazine capacity from seven to eight rounds, and the addition of a lanyard ring. A number of cosmetic changes were made to the pistol during its production life, including changes in the location and configuration of the slide serrations, and several variations in the hammer. The 1902 Military Model came closer to meeting the Army’s needs, and it was produced commercially until 1927, but it still was not the final answer.

Part of the problem, as seen by the Army, was the small caliber of the pistol. The .38 ACP round was hardly a pipsqueak, with velocity and energy levels that were superior to .38 Special. Nonetheless, the Army had determined that nothing smaller than a .45 caliber handgun round would deliver sufficient power for a sure knockdown. It is ironic to note that the thinking on military handguns has now gone full circle. The newly adopted Beretta, in 9 millimeter, returns to ballistics very similar to the numbers that were rejected back in 1902.

In 1905, Browning and the Colt factory made another step toward meeting the Army’s requirements with the development of the .45 ACP round. The Model 1905 pistol, made for this new round, was a scaled up version of the Model 1902. When the Army tested this basic design in 1905 and 1907, the results of these tests were finally encouraging enough to generate real interest in a .45 caliber automatic pistol. A formal competition was scheduled, with the promise of a rich contract for the winner.

The formal competition drew several other entries, including serious challenges from Luger and Savage Arms. Browning, in turn, continued to introduce refinements to the Colt pistol. A grip safety was added in 1908, followed by a major development in 1909, which brought the pistol to the brink of final success. The two-link system relied upon the slide block key to hold the entire pistol together. If this block should happen to fail, or if a careless shooter should happen to fire the weapon while the block was not in place, the slide could blow off, right into the shooter’s face! To solve this potentially deadly hazard Browning devised the single link recoil system. The new configuration replaced the front link with the barrel bushing, which encircled the barrel. The bushing was locked into the front of the slide, and it was held in place by the recoil spring plug. This system resulted in much greater safety and reliability, and the competitive pistols soon fell by the wayside, unable to match the performance of the Colt.

In 1910 the final prototype for the Model 1911 pistol, incorporating the addition of the manual safety lever, was put through an exhaustive test regimen. At one point, six thousand rounds were fired through a single pistol without a single jam or failure. On May 5, 1911 the Colt pistol was officially accepted as the “Automatic Pistol, Calibre .45, Model of 1911.”Following its adoption by the Army, the M1911 was also accepted by the Navy and the Marines. It was also adopted by Norway, for use by their armed forces. Supplemental production capacity was set up at Springfield Armory, in order to meet the heavy demand for the pistol. When the United States entered World War I, demand for the pistol was so great that contracts were let out to several other manufacturers. Only Remington/U.M.C. actually went into production, however, before the war ended, resulting in the abrupt cancellation of all outstanding contracts.

In service, the pistol was widely used as a side arm by officers and non-coms, as well as by such specialized units as the Military Police. It won a reputation for ruggedness, reliability and effectiveness, but a few more improvements were still to follow.

It was found that the pistol was somewhat difficult to control, especially in situations which required rapid fire. John Browning collaborated with the engineers at Colt, in what was to be one of the last projects of his lifetime, and the resulting modifications brought about significant improvement, without altering the basic design. In fact, all but one of the modifications involved components which were interchangeable with parts from earlier pistols.

The modifications made to the M1911 are described as follows. The main spring housing was arched and checkered, in order to fit the hand better, with a more secure grip. The grip safety tang was extended, in order to reduce the “bite” of recoil. Beveled cuts were machined into the frame, behind the trigger, in order to provide a more comfortable fit, and the trigger, itself, was cut back and its face was checkered. Finally, the front and rear sights were widened, in order to provide for a clearer sight picture. These changes were all adopted in 1924, and the designation of the pistol was changed to “Model 1911A1.”

Because all of the modifications, except for the cuts in the frame, involved component parts or sub-assemblies, the years between the two World Wars saw the use of surplus M1911 slides, mated to M1911A1 frames. The resulting “Transition Model,” as it is known to collectors, is a highly prized item, indeed. Of somewhat less interest, though no less authentic, are those M1911 pistols which were returned to depots or arsenals during their service and modified, using M1911A1 parts.

Following its adoption by the military, the pistol was also placed into commercial production. In addition to the .45 caliber pistols, it has also been produced in .38 Super and in .22 LR caliber. Other variations have been developed, including the lightweight “Commander” versions and the “National Match” pistol, with greatly improved accuracy and target sights. Colt has produced well over 3,000,000 pistols, and during World War 11 it was built under license by Remington Rand, Ithaca Gun, Union Switch and Signal Co., and in very small numbers by Singer Sewing Machine Co. Argentina also built both licensed and unlicensed versions of the pistol. In Spain, it has been copied by Star and Llama, and copies have also been produced in Poland and the Soviet Union. The original patents have long since expired, and in recent years Essex Arms, Arcadia Machine Tool Co. (A.MT), Randall Arms, Auto Ordnance, M.S. Safari Arms, Arminex, Springfield Armory (the private company), and others have all built their versions of the pistol. The compact and sophisticated Detonics pistol is a descendant of the original design, and the end of the line for the M1911 and its offspring is nowhere in sight.

Modifications to the pistol are also possible, and many of them can be accomplished by the home gunsmith. Such modifications can produce an “accurized” target weapon or a highly customized weapon for various forms of competitive shooting. Indeed, the shooter can literally design his own pistol in order to suit almost any preference.

BIBLIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

For those who wish to learn more about the pistol or its history, we recommend the following sources:

Colt Automatic Pistols, by Donald B. Bady; Borden Pub. Co.

John M. Browning American Gunmaker, by John Browning and Curt Gentry; Doubleday & Co. Handguns of the World, by Edward C. Ezell; Stackpole Books

Know Your Colt .45 Auto Pistols, by Hoffschmidt Blacksmith Co.

Syd Weedon, The Sight M1911, History of the M1911 Pistol

John Caradimas, M1911 Web Site, http://www.m1911.org

Sam Lisker, The Colt Auto Web Site, http://www.coltautos.com

Dave Arnold, “The Colt 1911/1911A1,” Guns & Ammo: The Big Book of Surplus Firearms, 1998.

Oliver de Gravelle, Model 1911.com WWII production of 1911A1’s by Colt, Remington, Ithaca, and Union Switch.

Comments, suggestions, contributions? Let me know