By Jim Higginbotham

The Browning designed 1911 pistol is arguably the finest close quarters combat pistol ever made. It is also the most modified or customized pistol ever made. Some of the myriad of changes made to John Moses Browning’s masterpiece are indeed enhancement but not all that glitters is gold. So, let’s take a look at what is out there and just what utility it might serve.

First off, let me say that this is not a piece advising you to modify your personal pistol. You should be aware that there is some debate on whether it is advisable, from a legal liability standpoint to do so. The idea is that should you be forced to use your pistol in self defense the prosecutor, should there be one, might make a case that you were irresponsible and were so interested in guns that you were just itching to use it. I don’t personally put much stock in this argument but never the less it is out there. At any rate I am merely discussing the various modifications and their effects and will leave the decisions on your own weapon to you alone.

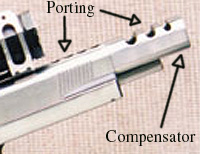

Secondly, I should point out that I am not discussing the various mods that are mere affectations or strictly meant to be used in competition for I am about the serious use of the handgun. Nothing at all against competition and gadgets here it is just that I am not discussing this except for some overlap in features which can be used both competitively and in the real world of shooting to live.

With that out of the way let’s start with the basics. There are many 1911 clones out there so let me specify that we are discussing the real military pistol or the equivalent Colt commercial Government Model for the most part. Actually the 1911 or 1911A1 is a fine pistol just the way it came way back when. The most obvious drawback to it was that the sights are so small (slightly larger on the A1 but you would hardly notice). One who really knows his Colts knows that there was a 1/10 inch optional front sight (fixed rear) available on request and that there were several pistols actually shipped with this option. So far as I am concerned, with this option, you have just made an original 1911 a 9.5 on a scale of 1 – 10. The rest of the discussion is how to make it a 10. Now one may legitimately ask about the trigger pull but nearly all of the real 1911s I have seen ( those not reworked by some arsenal or have been “repaired”) had triggers in the 4-5 pound range. One really doesn’t need much better though a lighter trigger might be desirable as we inch toward that “10”. There are also some commercial equivalents to the early guns available today. One such pistol is the Colt 1991A1. Right now its future is in doubt but as an example it is quite a pistol. I have examined several dozen of these ( usually in the process of customizing them) and I must say almost all ran right out of the box, the sights are decent and the trigger pulls were just about 4.5 pounds on average. I might want a more robust rear sight – since I walk into walls a lot – but that is sort of picking nits. I might also want to enhance it’s accuracy just a little – though it is certainly more than adequate for defense and to take off some of the sharp corners. Another pistol that comes about ready to go out of the box is the Kimber Custom Classic. Yet another is the Springfield Armory 1911s, though these might use a little work on the feed system in order to function reliably. No doubt there are others so don’t take my not mentioning them as a slam on these other brands.

If you happen to have a pistol which has the minimal requirements of highly visible sights and manageable trigger then there are many options open to you. A good sturdy set of sights which are snag free will cost you somewhere between $50 and $100 installed. Tritium night sights ( which will last about 10 or 12 years) are a bit more and, while nice, are not essential. Adjustable sights can be up to $250 or even $300 but in actuality they are a disadvantage, prone to breakage and they tend to get “unadjusted” as well as adjusted. Most serious gunsmiths that I know have fixed sights on their personal 1911s. A good crisp 4 pound trigger job will run anywhere between $40 and $100 from a reputable ‘smith. Don’t take chances here, an unreliable trigger is dangerous.

OK, so we have a basic pistol which feeds ball ammo with monotonous reliability ( to insure this always use quality magazines), has sights which are at least 1/10″ wide (.100″), .125 is better, and at least .140 – .200″ tall, and has a reasonably crisp 4 – 5 pound trigger. Noting that there are 1911s from custom smiths out there that cost up to $3,000 you might inquire – what am I getting for my money? I will attempt to tell you, without stepping on the toes of too many gunsmiths – most of whom are dear acquaintances to me. In some case the news is not good though.

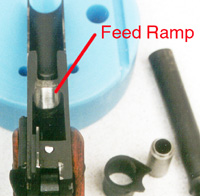

To my mind the priority goes to function. The original military weapons ( and Colts up to about 1969) were not noted for feeding unusual ammunition such as semi-wadcutters and the newly designed hollowpoints ( oddly enough the ammunition manufacturers have only recently discovered that they can make JHPs with a roundnose profile which feeds just fine in older guns). So the first major consideration after sights and trigger are modifications which actually enhance the reliability of the weapon. A gun that won’t work under the worst possible conditions should be repaired or thrown away as it is a danger to the shooter. Most smiths offer a “reliability” package which usually consists of modifying the feedway ( both in the frame and barrel), polishing the breechface and adjusting the extractor tension as well as removing sharp edges from the extractor “hook”. Not everyone can do this work so be careful. Don’t let anyone tell you that the separated feedway in a 1911 ( part in the frame and part in the barrel) is a big disadvantage – it is not. Nor is it necessary to have a “ramped” barrel to have a chamber which supports the case head for some of the hotter loadings ( however many commercial barrels – either ramped or unramped – do not support the case head so be careful with +P loads).

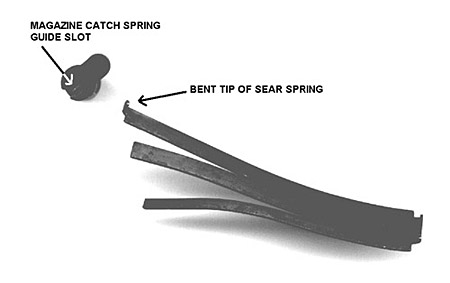

Leaving accuracy enhancing modifications for later ( I will explain why) lets look to the Controls on the pistol. Likely the most common modification in this area is the thumb safety. Most people want a larger safety to enable them to disengage it more surely when speed is of the essence and in a fight for your life speed is usually of the essence! Many want to augment this with an ambidextrous safety which can be manipulated by either hand. Such modifications are fine and even desirable, however there are some pitfalls. Most common is that just drop-in in a safety can leave you with basic controls that have sharp edges and can cause problems with your handling of the weapon. Some are even sharp enough to lacerate the skin. Another is that if the safety is too large – especially on the right side of the frame for right-handed people – then it can get inadvertently disengaged. This is one reason I do not opt for “bilingual” safeties on most of my 1911s. Not that it worries me too greatly to find I have bumped the safety off. Good gun handling and a good holster are the essence of firearms safety not the mechanical device too many have grown dependent on. Of all the safeties on the market I am most impressed with the Chip McCormick speed safety. It is extended but it has no sharp edges and literally “melts” into the gun. Yet there are other good safeties if you want to put in a little work de-burring them. One must make sure that they actually function, I have seen many a “custom” 1911 which would drop the hammer when the trigger was pulled with the safety off ( usually they drop the hammer when you release the safety and usually they do not fire but it is scary).

These days a popular control modification is to replace the grip safety with a wider version that not only helps to spread the recoil over wider area of your hand but also allows a higher grip on the weapon which is an aid in controlling recoil. Done correctly this enhances the handling of the pistol though I have never noticed that it has a great effect on my shooting a particular drill it helps to make those long practice sessions more pleasant and a higher grip is a good thing. Again, you want to make sure the safety functions. The most common problem I see is that the shooter will fail to disengage the safety with his higher grip. Many such safeties now come with a “speed bump” on the lower part to help insure disengagement. Years ago many folks pinned their grip safeties – Jeff Cooper, the Father of the Modern Technique was prominent amongst them. Personally I don’t see any need to do this since the grip safety surfaces can be “adjusted” to disengage at the slightest movement but then again, I don’t depend on mechanical devices for my safety so it does not bother me much to see an inoperable grip safety. Mine work since someone else might be shooting my pistol and expect it to work.

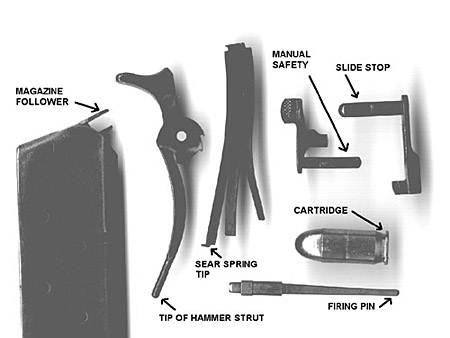

Then there is the slide stop. Now we start to tread in dangerous waters. A thing as simple as a slide stop can end your life. The purpose of the slide stop is – of course – to stop the slide from closing when the last shot is fired. The trouble arises when the part stops the slide BEFORE the last shot is fired – sometime the first or second! One sure way to invite such a problem is to install and extended slide stop – or even worse – ambidextrous extended slide stops! Not only are these not usually well made but the fact that they extend back nearer the firing thumb makes them more likely to be inadvertently engaged by that thumb in recoil. This is very bad as you might imagine. To install one of these dinguses on your pistol is to mark you as a tactical amateur anyway. First, and more importantly, the thinking gunman reloads anytime he CAN – meaning the first chance he has when bullets or people are not coming his way – no matter if he has fired 2 rounds or 6, get the gun back up to capacity just in case the Bad Guys have help! The second thing, recognizing that we all can’t count rounds in a gunfight ( not something I try to do anyway) and that comes the day we actually do run dry – no problem, just speed reload ( from behind cover please) in the normal fashion and trip the slide release with the thumb of your weak hand – which just seated the magazine and is in perfect position to do so. Or, as is the current rage in tactical schools ( in order to have a uniform movement between all autopistols) simply retract the slide with that hand and release it. In plain words, avoid this modification like the plague.

One other possible modification to the slide stop is to “dimple” or slant the bearing surface where it meets the plunger. This helps to ensure that normal recoil will not inadvertently engage the slide stop and yet allows proper function with most magazines ( some 8 rounders may be a little week). I don’t regard this as a must unless you have noticed the problem in your particular gun.

Yet another control on the 1911 is the magazine release. Here too we can get in real trouble. In order to enhance their ability to reload faster, many folks have given up sure function. Reloading is something emphasized in competition – and indeed it should be a skill one has – but it is highly overstated. I have only recorded two cases in which a person was able to finish a fight in better shape because he reloaded quickly ( and both should have been over long before the reload) in my decades of research. Gunfights tend to be over in 2 to 3 seconds, reloading is not one of those things that figures highly in them though, to be sure, there are a couple of cases where failing to reload might have been a problem – Newhall comes to mind. The great danger in an extended or enlarged mag release is that it will get bumped in the holster and the mag will be released without your knowledge leaving you with a single shot pistol ( it is even worse with a S&W since the gun won’t work with the mag down 1/4″ ). Best leave the mag release alone. The Kimbers have a slightly extended button which I can live with but otherwise leave it alone. Left- handers can actually operate the standard button better than right-handers so ambidextrous releases should be avoided also.

While I know many are champing at the bit to hear about some of those “extreme” gunsmith mods and little secrets to tuning race guns, bear with me while I talk about really important stuff. Externally your gun should feel like a well used bar of soap ( though not necessarily slick). Meaning, it should not have any razor sharp edges that cut hands, clothing and leather – or plastic these days. You should be able to comfortably run your hands all around it. The only thing that should stick to your hands is the actual gripping surfaces of the frame. Old Colts and military 1911s are usually OK in this regard but even they could use a little “dehorning”. Modern commercial Colts – especially the Enhanced models which I refer to as “disenchanted” models – and Springfield Armory’s as well as several others are pretty poor in this regard. One exception is the Kimber. Almost all the edges ( if you don’t count the recoil spring plug around the goofy guide rod) are nicely blunted without exaggeration. Make sure your weapon does not hurt you to handle and shoot. It is a hand tool, it should be comfortable.

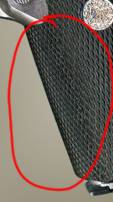

One thing I like that sounds out of place when talking about bars of soap, is either stippling or checkering on the front and back straps of the frame. Checkering on the stocks is something I can take or leave. The gripping is done fore and aft on a 1911 and these surfaces should be non-slip. Some folks get by on the cheap by applying some skate board tape or other rough temporary surface. Some even just glue sandpaper to the surface – “True Grit”. Good checkering is not only practical it is very attractive. It is also expensive running about $150 to the inch. Stippling works just about as well and I personally like it but it is a bit too rough for some folks taste. I am not fond of wrap around rubber grips with either checkering or finger groves. This does not release the gun easily enough when the grip is relaxed to perform a reload nor does it allow enough leeway when establishing the grip on the draw. If you do like them I can think of no really serious drawbacks except to warn against any stock that covers the toe of the magazine when it is inserted. You might need to use this protrusion to strip a stuck magazine out of the gun in case of dirt or a double feed. Obviously stocks with thumb rests should be avoided since they block access to the magazine release.

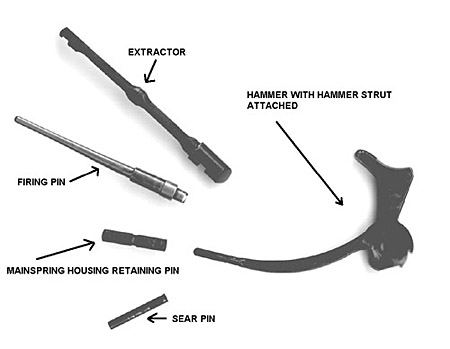

Though not really controls, let’s examine some of the various accessories one is tempted with when perusing all those gun magazines. How about starting with hammers. There are literally dozens of shapes and sizes of hammers. For the most part I think this is strictly a matter of taste with the exception that if you install a high and wide grip safety then you will likely need some sort of “commander” hammer to fit with it. Functionally I can find nothing wrong with the standard G.I. hammer. If it bites you then “bob” it by about ¼” . However if you want one of those high / wide grip safeties then you will have to install a hammer that will accommodate it. A “Commander” hammer is in order and there are many out there. Most of the top names, Wilson, MGW, McCormick, etc. are well made and you can simply pick one whose looks suit your taste. Many of these relocate the hole that the strut pin anchors through in the manner of the Gold Cup since that takes a lot of load off of the hammer as it rests on the sear, resulting in a lighter trigger pull. Since the 1911 is carried in condition one ( cocked and locked) when in service it does not matter much if the hammer is easy to cock or not.

While we are on the rear of the pistol let’s look at the mainspring housing. You can have them in flat or arched or in between. Since the serious gunman uses the sights for the most part, this is a matter of personal taste and he can usually pick up a gun with a type of MS housing different from his and do quite well with it. However, even the sighted fire used in the Modern Technique is quite reflexive and a strange feeling pistol will slow you down a little – I simply could not live with my Glock 23 or 22 ( early models) because I constantly had to pause to push them down on target after a smooth draw. So, naturally I made them point more like a 1911. While I like the feel of the flat housing, I learned to shoot a 1911 with an arched so the vast majority of my guns have the arched. I prefer mine checkered 20 LPI. I also prefer mine to have the military lanyard loop. This is not so important but it is a nice touch to be able to attach a lanyard when you are canoeing or backpacking ( particularly if you sleep in a hammock on the trail). For self defense under normal conditions it probably does not serve a purpose. It does however, make a handy bottle opener – if there were bottles to open anymore. Another related MS issue is the Extended Magazine Wells that are so common today. Often these are part of the custom MS housing itself. Personally I think they are unnecessary for the serious pistolero. Sure they make hitting the mag well easier for competition but in real life you likely wont have to reload and you have made your pistol taller and less concealable. The main thing I have against them is that it makes using a standard magazine without a pad very difficult and almost impossible to reload with quickly. Hardly worth the effort for what little gain you get. One exception I have seen is on the Officer’s Model. By attaching one of the S&A mag wells which taper off before it gets to the “toe” of the magazine, on the OM you have extended the rear of the pistol which helps most normal hands get a better grip while extending the front none at all. This means the pistol is really just as concealable as before the way most of us carry our guns with the barrel canted to the rear. Gun designers should realize that when you sit a gun down with the floor plate of the magazine flat on the table, then the barrel should be parallel to the table not pointing up ( or down). This is the way the hand is shaped and it promotes concealability. At any rate the OM with magwell will take a standard 1911 magazine without a pad and you won’t fail to seat it. A word of caution, longer mags in an OM can malfunction if you put upward pressure on the floor plate while firing so don’t use the “cup and saucer” grip.

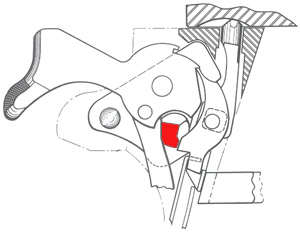

Let’s move up to triggers. We have talked a bit about trigger pull but let’s discuss the part. There are many triggers available and most of them are fine so I would say, if you want to change your trigger at all, then pick the one that suits your hand and your tastes. Stay away from the cheap ones with aluminum trigger stirrups but the material of the trigger itself is almost irrelevant. At first I thought plastic was a bad thing but I see that it moves easily and is almost indestructible. I still prefer some sort of metal for taste or perhaps to prevent melting in an extremely hot environment ( I mean where you might store the gun not for me as anything that would melt the trigger on my Kimber would melt me). The most important characteristic of the trigger, after assuring that it fits your grip style, is the actual weight of the part. Not so important for shooting but when you reload from slidelock or drop the slide on an empty pistol ( this is NOT a good idea but likely someone will do it to your gun sooner or later) the inertia of the trigger – it’s tendency to stay still – will trip the sear when the gun lurches forward as the slide slams shut. This causes the hammer to “follow” from the jar and usually it will catch on the “half cock” notch ( safety shelf on series 80’s). This is not a good thing. Choose a good gunsmith for your trigger job and choose a light part for your trigger.

Speaking of slides slamming forward, let’s talk about recoil springs. This is another area where you can get into trouble with the neat gadgets available in parts ads. Let me state right up front. A recoil spring guide rod is not one of the stellar ideas to dawn on gun designers in the 20th century. You will not that none of John Browning’s designs have them. That is because they are not needed. To be sure, some guns work OK with them, Glock, S&W, Kimber, Wilson ( who makes guns both ways) etc. The problem is twofold. One is reliability. If they are designed well, as those in the aforementioned pistols seem to be, then fine. However some after-market designs are not well thought out. It takes more than just sticking a rod through your recoil spring. In the 1960 there were several after-market rods that sold through mail order which were less than stellar – we called them malfunction kits. You could put one in you Colt that was monotonously reliable and then get a chance to do remedial action drills. The more pertinent point is that the rod under the barrel prevents you form applying pressure under the barrel to draw the slide back, preventing convenient one hand operation. If you find one hand disabled or occupied during a gunfight and you do need to clear a malfunction, reload an empty gun from slide forward ( slide stops don’t always work) or simply need to check the condition of your weapon you can place the recoil spring plug on the edge of a table or desk or the sole of your shoe and press the slide back by using only one hand. Another handy trick is to “press check” your piece in the dark by pinching your thumb to the inside of the trigger guard ( just the tip and not too far inside please!) and the index finger under the barrel ( you approach this from the underside and NEVER let actual muzzle point at your finger). With seemingly little pressure you can bring the slide back about ¾” which will allow you to take your trigger finger ( you have the gun in a firing grip) and feel the cartridge in the ejection port. There are other ways to do this that can be applied to guns with the rod but they are a little more difficult. Let me say. If you have a guide rod on your 1911 and the gun works then don’t feel like you have to rush out and get rid of it. These are sort of minor points. Besides, some of the compact models out there were designed with them and it would be difficult to change them.

OK, now what about recoil springs and buffers. The standard Govt. Model spring is 16 pounds. I am sure that the gun will work just fine with this if you replace the spring when it is worn out. The military uses the gauge of spring length. When the spring has worn until its uncompressed length is 5″ then it is time for it to go. Military parts these days are “low bid” so they were getting about 1,000 round on a spring before replacing them in the mid 80’s as the 1911 was being phased out of service. Personally I prefer an 18.5 or 20 pound spring for the 5″ guns ( 20-22 pounds for the 4.25″ guns) but one must be careful not to go too high lest he run into the problem of short cycling the slide due to a lose grip. The 1911 is one of the most forgiving designs I have ever seen – it will even function when held with 2 fingers or even held upside down – but all autos eventually have the point where less resistance to recoil will result in a malfunction. 18.5 pound springs work for almost everyone with normal ammo and they will overcome any slight resistance to feeding that perhaps a 16 would not. At the same time one does not want to go too high on the spring weight as there can be battering when the slide closes as well as when it is shoved to the rear. Stick with this range. While on the subject of springs, do not change the weight of the Main Spring ( the one that drives the hammer). Many amateur or even professional bullseye gunsmiths will cut or reduce this spring in order to make a light trigger pull easier to obtain. Don’t do it. The pressure of the hammer in its forward position is part of the lockup timing cycle of the slide, less resistance here means more battering and has much more effect on it that 4 or 5 pounds of pressure in the recoil spring.

What about recoil shock buffers. Well, I have experimented with these for years and was on hand when the Wilson version was invented – or at lest conceived. I can see the logic in this but over the years I have gradually gotten away from using them in my serious self defense guns. I do use them in my practice guns just to be on the safe side. The problem is, and it is different with each individual gun, that these things can get chewed up and spread out and cause the gun to become unreliable. This is a bad thing in a defense gun. I was having trouble with a Wilson Combat Master ( this was a $1500 pistol in 1985) running with ball ammo and McCormick magazines. Now the gun was good, the mags were good, the ammo was Winchester ball and the gun was clean when I started shooting it. Oiling the barrel hood made it run better but it still choked. I did not discover the problem until I got home. The shock-buff was smashed and a bit of it was pushing upwards on the underside of the barrel. Needles to say, that gun no longer carries a shock-buff. Yet they seem to work in some other guns. What is really needed is a sort of “sandwich” which has steel in front buffer in-between and steel in the back so that it won’t get chewed. However this can all interfere with the reward travel of the slide and the odds of the slide locking back on the last shot – especially on a Commander. Shock buffs may save your gun from battering if you shoot 1,000 rounds a week but it may also cause problems – buyer beware.

So far I have not mentioned barrels. I am not going to talk about them much. I strongly feel that most folks do not shoot quite well enough to appreciate the difference between a run of the mill barrel and a match barrel. My dad’s Remington Rand 1911a1 which is unmodified and was made in 1943 shoots about 5″ groups at 50 yards with ball ammo. My most accurate 1911 will do 1″ at this range but I doubt that I can tell the difference when shooting a man at 10 feet or even at 25 yards from a field position. However, some folks want a super accurate piece so that they at least know it is them doing the missing rather than the gun. My advice on barrels is this. If the fit of the bushing is not extremely loose and you cannot move the barrel by pressing down on the barrel hood while it is locked in battery then you likely don’t need a new barrel or bushing. If the former is true you might need a new bushing. If the latter you might get by with a new link ( it will not be locking up in the preferred manner though). My friend Dane Burns, who builds extraordinary 1911s, believes that there never was a G.I. or Colt Govt. Model to ever come out of the factory with a “properly” fitted barrel. One where the “legs” or bottom lugs of the barrel as well as the link rub evenly on the slide stop as it goes into lockup. I tend to agree with him though the law of averages says that there must be some which are properly fitted if only by accident. My point is that unless you want a pistol that shoots 1″ at 50 yards then you don’t have to have perfect lockup. The G.I. guns – until they are simply shot out – will have all the accuracy a person needs for self defense and a little fitting – even less than perfect fitting – can get you to 3″ at 50 yards which is much smaller than the front sight. I can’t see 3″ at 50 yards!

Barrels, especially the feedway and the chamber dimensions, affect the reliability of the gun. Here, the things that enhance accuracy – tight tolerances – work against us so we have to have a compromise of sorts. Dane’s guns are EXTREMELY accurate yet he emphasizes that they must work. He is one of the few smiths who can accomplish this. His guns also cost $2500 – and are some of the few that are worth it. However, most out of the box Kimbers will shoot 3″ at 50 yards and they usually work pretty good ( I have not had any gun related malfunctions out of either of mine since I bought them). One after-market barrel that I have experience with, the Wilson, seems to be very accurate and is cut with sufficient tolerance to work well, I don’t even have to modify the feedway in the barrel, though I do polish it just a little which is likely unnecessary. The critical lockup on a 1911 barrel is in the rear. The bottom lugs, I mentioned as well as the barrel hood should reposition the barrel the same every time. The bushing fit can be a little more loose than most people think. Whatever you do don’t buy a two-piece barrel and I would recommend replacing the two-piece barrel that comes in the Springfield Armory guns immediately. Bottom line here is that if you spend your $200 on practice ammo then you will likely find you have a much more accurate gun that you thought you started with.

Well this has gone overlong and though I have only scratched the surface I must stop. I hope it has given food for thought. Good shooting.

Praise the Lord and pass the ammunition.

See also Custom M1911A1 Modifications – A Pictorial Guide