The new Steyr M series pistols have excellent state of the art features, some of which cannot be appreciated until you actually test fire one. Read on if you want to find out more about this new millennium pistol series.

A Short Steyr History

Wilhelm Bubits is the mastermind of the Steyr pistol. He’s a hobby shooter who at one time worked for Glock, and was also a uniformed officer and later a plainclothes officer.

Basically, Bubits was always critiquing pistols and finally decided to become a designer, so he could build what he envisioned. He actually offered his patents to Glock and was told that his designs did not follow their “philosophy” of design.

So, Bubits ended up with Steyr Mannlicher, another Austrian arms maker, in 1997. A key player to bring Bubits’ dream into reality was Steyr’s engineer, Fridrich Aigner. After two years of research and development, the pistol has been christened.

Steyr Mannlicher has been making quality firearms since 1864. Ayoob sums up Steyr’s history well when he said that Steyr is a daring company that boldly goes where no gun manufacturer has gone before, and has been successful doing it.

For example: The Steyr Professional with it Cycolac stock was introduced 25 years ago and has changed the face of riflery, proving the superiority of the synthetic stock. And the Steyr AUG was the first extremely successful tactical rifle. Instead of just a custom-make of Jeff Cooper’s Scout Rifle, Steyr dared to actually manufacture it. And everyone who shot it, has marveled at its execution.

So, with Steyr’s two years of expensive development of the M series pistol line, I’m expecting to see an excellent new product that will not have to bow down to the competition.

The Steyr M (Medium) Series

My Steyr Owner’s Manual lists three M models: the M40, M9, and the M357. I was told by Steyr’s exclusive US importer, GSI, that the M357 will be out in 2000. The M40 has been out since Nov ’99 and the M9 came out a month later. The M357 is scheduled to hit the market in June ’00. You can contact GSI at www.GSIfirearms.com or call 205 655-8299. The Steyr M series pistol has been Americanized with a stamping on the side of the frame, “GSI, T’VILLE, AL” (that’s Trussville, Alabama).

There are plans to also expand the line into the “S” Small series, and this series might possibly see daylight in 2000.

Rumors from the Jan. 2000 Shot Show: I was told some interesting information from someone who attended the show and had spoken with Bubits. Besides the “S” series, Bubits talked about a Steyr .45. He mentioned that the .45 would use regular 1911 style 8-round magazines. This model may be shown in the 2001 Shot Show.

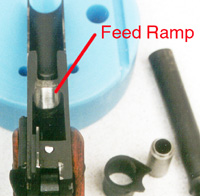

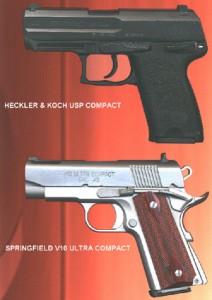

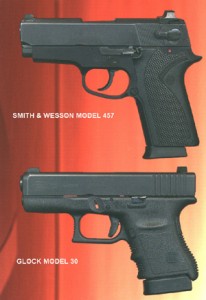

Unsupported Versus Supported Chambers

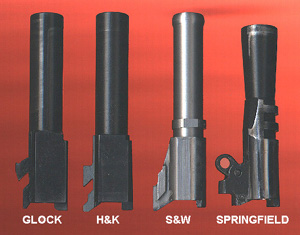

The Glock was born as a 9mm and then modified into the now famous Glock 22 and 23 .40 S&W models. The Steyr M40 was born as a .40 S&W pistol and then the 9mm version was developed. That’s why the Steyr M40 is exceptionally beefed up with a very strong lock-up system, and why it has a “well supported chamber”.

Some manufacturers of 9mm pistols simply rebarrelled, modified the breechface and put in a stiffer recoil spring to develop their initial .40 S&W pistols. Since the .40/10mm bullet is bigger than a 9mm, the only way to get the .40 to feed reliably was to create an intrusive feed ramp, and possibly an oversized chamber to match. Thus the .40 S&W “Unsupported Chamber” was born. This was a quick and dirty fix by some manufacturers to get to market fast.

Other manufacturers either started from scratch or went through the added expense to redesign their 9’s to safely handle the .40 with a well-supported chamber that still feeds reliably. These types of .40 pistols are therefore safer to use, whether you shoot factory ammo or reloaded ammo.

If you want to find out if your .40 has a well supported chamber, then do this: Measure the diameter of the lower, most expanded part of some fired brass. After the first measurement, rotate the brass slightly and measure it again because the brass sometimes measures greater from a certain angle because of the 6-o’clock chamber opening affect. If your brass measures .431 or greater, then your chamber is entering into unsupported territory. Also, put a round into the barrel and look at the 6-o’clock position of the chamber opening. If the thin part of the brass wall is exposed, or too much brass is exposed, you have an unsupported chamber. “Both” of these measurements are important to determine if your chamber is well supported or not. The greatest

brass expansion occurs when shooting full power loads.

In the six-o’clock chamber opening of the Steyr M40, you see virtually “no” exposed brass and the chamber is not oversized either. I kid you not! This is truly amazing, especially since the rounds feed perfectly. A Steyr barrel does not over expand and bulge the brass like an unsupported chamber would.

The diameter of the Steyr fired brass measures around .428 -.430 for full power loads. The Glock .40 and even a SW99 I tested can expand brass as much as .431 .433, which is a huge difference. In other words, the Steyr M40 is friendly for using in sports, reloading, and in agencies. It should give a little extra confidence to anyone who carries a .40 caliber pistol.

Generally speaking, ammo and gun companies don’t care about reloading safety and case life. Some of the newer reloading manuals have strong warnings about reloading for pistols with unsupported chambers, especially concerning high-pressure cartridges.

One positive side effect of Glock’s famous unsupported chamber and their marketing omnipresence, is that some ammo companies have beefed up their .40 S&W brass so it has a better chance of surviving when fired in a Glock chamber.

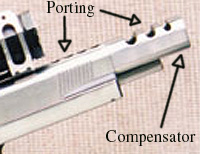

The Barrel

Conventional rifling is used in the barrel, for those that choose to use lead. Bubits has stated that for the cost of being able to use lead and be “handload compatible”, there is no more than a 3 percent to 4 percent loss in velocity.

The Steyr M series employs the Browning cam-operated tilting barrel system to lock the action during firing.

For Lead Bullet Fans

I performed a little test just for you. I don’t normally shoot lead because I find it a little too messy. I bought 100 Oregon Trail Laser-Cast 170 grain Semi Wad Cutters (SWC).

Now, I’ve never been able to get SWC rounds to feed consistently in any of my Glock .45’s. I’ve had some luck shooting SWC’s in Glock .40’s as long as the right combination of magazine spring tension, magazine follower type, etc are stumbled upon.

I’m glad to report that my Steyr M40 fed all 100 SWC rounds “perfectly”. This is great news for sports shooters since a semi wad cutter cuts a larger, cleaner hole in the paper. That’s because a SWC is not only a flat point, but it has a 360 degree cutting shoulder that maximizes the size of the hole. Now I just have to find some good bulk plated/jacketed SWC bullets.

The Trigger

The Steyr, like the Glock, has a safety on the trigger. If the trigger gets bumped from various angles, the trigger will not release. You need to put a positive finger pressure on the front of the trigger for the gun to fire. This is an important safety feature that some people just don’t get.

After shooting a few hundred rounds, I took the slide off to clean the M40. I put a little high tech Tetra lube on the inner trigger workings with a q-tip and then lightly removed any excess lube with the dry end of the q-tip. Oh, and I applied a little tetra to the long trigger bar as well. After reassembling the Steyr, the trigger action is silky smooth. Early triggers had about an 8 lb. pull. After August, 2000, the standard trigger pull became 5 lbs.

The trigger guard is angled 10 degrees downward, leaving room for a manual safety. This trigger angle allows for a very natural, higher finger placement.

The Steyr trigger is true double-action since the trigger continues to cock the striker throughout the stroke until it is released. The Steyr trigger does not feel like a typical double-action trigger at all. It has a short stroke action (aprox. 1/8″) with a very short reset, for very accurate rapid fire.

Like the Glock, the Steyr striker mechanism is under partial tension (partially cocked) when the trigger is fully forward. After the trigger is pulled, the striker is fully at rest until the trigger is reset. The three passive safeties keep the Steyr pistol safe to operate. You just have to remember to engage your primary manual safety, the one between your ears, and NOT put your finger on the trigger until you are ready to fire; this rule is actually true for ALL guns.

In my opinion, the short, clean, stroke of the Steyr trigger feels better than the longer, mushier Glock trigger. I even grabbed a Glock armorer at my shooting range so he could test fire the Steyr. He agreed that the Steyr trigger felt better and the perceived recoil was less. But he told me not to tell anyone

The new SW99 pistol has some different trigger modes as well. But I find its trigger pull way too long for my preference, although some people seem to like it. Maybe, if a pistol does not have a manual safety, the longer pull is considered safer, although proper training is the real answer. For example, the classic 1911 style single action pistol is perfectly safe as long as one is properly trained and practiced at thumbing the safety off and on during the firing and holstering sequence. Each trigger style apparently has its aficionados

Since the M40 has a short trigger pull, it might be more appropriate to compare it to a single action trigger. Of course the M40 trigger cannot match a finely tuned single action trigger. But, for a short stroke DA trigger with 3 passive safeties, “requiring” no manual safety, unlike a single action pistol, it comes darn close. I’d say that single action fans could adjust to the new Steyr M series pistol pretty easily. Don’t forget! You can use the Steyr manual safety if you want to. The safety features are covered in depth a little farther down in this review.

Trigger Guard

The front of the large trigger guard is textured so those that like to grip the front of the trigger guard will have a non-slip surface.

Take-Down Lever

Step 1: To disassemble the Steyr, you must first check to make sure the pistol is empty with no cartridge in the chamber and no magazine inserted. Then you have to pull the trigger, like the Glock, in order to release tension to the striker mechanism, pointing in a safe direction of course.

Step 2: The take-down lever is quite easy to use — somewhat similar to a classic SIG. You simply press in the integrated lock button slightly, which is next to the take-down lever, and then the take down lever can be swung down easily so the slide can be removed. When the slide is reinserted onto the frame, the take-down lever automatically pops into place. Very clean.

A person unaccustomed to a Steyr may very well think the take-down lever is the manual safety, especially with the bold “S” and “F” markings adjacent to it. This could give the owner just enough time to take control of the situation during an emergency. With the manual safety on, this situation could get downright confusing for a perpetrator.

While a detailed disassembly is the job of a Steyr trained armorer, I can give you a rough idea of how to do it. Behind the take-down lever is a diagonal disassembly mark. You line up the take-down lever with this mark. After removing the manual safety, and depressing the integrated lock button, the entire modular steel housing can be lifted out of the frame. This entire process can be accomplished within seconds.

Grip

The grip has one finger groove that should fit almost all hand sizes, large and small. The upper rear of the grip frame is dished out, somewhat similar to the Beretta guns. This allows the web of the hand to get in a little tighter and also makes reaching the trigger easier.

Actually, some people who are used to oversized, large grips may at first complain that the Steyr grip is too small. I’m sure that grip socks will be made available for the Steyr to satisfy the needs of some owners. I’m 6′ 1″ and have long fingers, And I find the Steyr quite pleasant to shoot.

The grip angle is 111 degrees. Basically, this means when you aim the Steyr, you don’t have to cock your wrist up or down since it is a natural point shooting pistol. The bore axis is so low (lower than a Glock) that it’s almost like pointing your finger. A nice side effect is less felt recoil as well.

The textured pattern on the grip is adequate to obtain a nonslip grip. I personally like the more radical HK USP grip texture that almost feels like sandpaper — but some people think that’s a little too much. At any rate, the grip shape, along with the textured pattern, fits my hand perfectly.

Magazine Release

The magazine release is well placed on the left side of the frame so it’s easy to reach for a right or left handed person. When the pistol is laying on it’s side, the magazine release button is out of the way so it won’t release accidentally. The magazine release does not have sharp edges like the Glock does.

Magazines

Steyr magazines are steel and drop-free. Since the double-column magazine is tapered, it fits easily into the beveled magazine well. The bottom of the magazine well has room to pull out a magazine should that ever be necessary.

Out of curiosity, I loaded a .40S&W magazine with 10 357 SIG rounds. They seemed to fit very well. I’m hoping that the magazines will be interchangeable like the excellent Sigarms magazines are with either caliber.

New Steyr magazines are a heck of a lot easier to work with than a new Glock magazine. I typically can only get 8 cartridges in a Glock magazine for the first week or so until the magazine spring starts slowly breaking in.

Magazine Catch

The magazine catch is made out of metal, not polymer. So the high-quality steel Mec-Gar magazine directly contacts a metal magazine catch. You will therefore not have a problem of the magazine catch wearing out.

I’m only aware of two torture tests so far. One is discussed in detail later in this review, in which Bubits pumped 10,000 rounds through one M40 within a two-day period. GSI also shot over 13,000 rounds through several M40’s. The pistol parts are holding up very well as of this writing.

Accessory Mount

The Steyr accessory mount on the frame, for light mounts, etc, has two rectangular cut outs on each side of the frame, instead of the typical rail. These recessed slots allow the mount to have a positive attachment, with no movement whatsoever, and it gives a very distinctive look to the Steyr pistol.

Slide

The slide is super hardened with a tennifer finish, similar to the Glocks, and then a dull blackened finish is applied. The grasping grooves are well spaced, giving the shooter a comfortable contact when operating the slide. When you rack the slide, it is quite smooth.

The Steyr slide is only 18 ml high compared to the Glock’s 22 ml.

Slide Stop

The slide stop has a generous 30 degree angle making it very easy to manipulate. The owner’s manual states that the strong slide stop can be used to release the slide, if you prefer not to rack the slide.

Slide Rails

The slide rails are not molded into the polymer frame like a Glock and other polymer brands. The Steyr is essentially a steel pistol, wrapped in polymer. The mechanical parts function on a steel sub-assembly, and the lock bridge is very “strong”.

It’s interesting to note that the rails are cut at a 45 degree angle. This allows the slide and barrel to ride about 1/8″ lower than existing pistols with rails cut at 90 degrees. The Steyr bore axis is about 5mm lower than a Glock. As a result, there is less muzzle flip, less felt recoil, and the low bore axis helps to center the round coming out of the magazine into the barrel chamber.

I shot the Steyr M40 side-by-side with a Glock 23 and the M40 did have less felt recoil.

Sights

The standard Steyr comes with fast acquisition, triangular-trapezoid sights. They can easily be swapped for traditional sights or night sights. Trijicon has mentioned they will support the new Steyr pistols by late 2000.

I personally believe these standard stock sights are the best I’ve had on a pistol. It’s so easy and fast to find the large, triangular front sight during speed shooting — wonderful. For accuracy shooting, use the tip of the front triangle for superb accuracy.

These standard front and rear sights are steel, unlike the Glock, which uses plastic sights (the front Glock sight is especially fragile).

The Steyr has a sight radius of 6.22″, compared to a comparable sized Glock 23/19/32 with 6.02″.

Loaded chamber Indicator

There is a loaded chamber indicator in the back of the slide that can be seen or felt.

Inside the M40

When I looked inside of the Steyr, I was pleased to see how strong and beefed up all the parts are. This is one tough gun that is excellently engineered to last a long time.

5-Point Safety System

The Steyr pistol has a manual safety for those that are concerned about retention issues. You can use it or not. The Steyr manual safety is very similar to several popular rifles that use a similar safety. More on that below.

The Steyr has three passive reset action safeties so it can be carried safely without using the manual safety, if desired. Along with the 3 reset action safeties and the manual safety, there is an integrated lock (for storage purposes), giving the Steyr an impressive total of 5 safeties!

The integrated lock is next to the take-down lever, located on the side of the frame, and comes with two keys. The police version uses a handcuff key. The civilian version uses a two pronged key. When it’s locked, you cannot pull the trigger or take the pistol apart, but you can load and unload the pistol.

The integrated lock is not meant to be used in speed drills. You carefully insert the key and push the lock in then then rotate counter-clockwise to lock the pistol. You then push the lock in and turn the key clockwise to unlock the pistol. During the unlock phase, it’s best to keep turning the key clockwise until you feel pressure as you pull the key out so the lock pops out into position easily. It’s a snug fit. You can also pull the slide back a little or lightly press the trigger to help pop the lock out into position, although these two latter methods are non-standard and should not be necessary. The manual safety can be on/active during the use of the integrated lock for extra safety.

I have actually started using the integrated lock when I do not have direct control of the pistol since it is so convenient. Obviously, during concealed carry, you do not want to use the integrated lock! As a side note, the integrated lock is a very inexpensive part and very easy to replace.

Of course all locks can be picked with the right tool, even the generic handcuff lock. Overall, the integrated lock is an excellent feature, and it sure beats misplacing an external lock or forgetting one during transit.

I really like the Steyr manual safety because you don’t have to worry about toggling it on and off accidentally. And it’s basically invisible if you choose not to use it.

During a scuffle, or an operator slide rack error, or if the pistol skids across the floor, a typical manual safety on the side of a slide or frame can sometimes be toggled unknowingly. A Steyr manual safety system is less likely to be affected by these same scenarios.

For pistol owners in general, the Steyr manual safety is a bit different from what they are used to. On the other hand, there are a number of rifles with the safety in the same general location as the Steyr pistols: M-1 Garand, the M-14 or Springfield Armory M-1A rifle, or the Ruger Mini-14 or Mini-30. And the new Vector pistol from South Africa employs a similarly placed manual safety.

To activate the manual safety, you pull down on a small lever on each side of the frame. Interestingly, these two levers are in the same basic position as the Glock take-down levers and they are protected by a slightly recessed polymer molding. This action lowers a small safety bar from the “top” of the trigger guard. Note: If the trigger is in the fully back position, you cannot activate the manual safety since the trigger is already deactivated.

You would normally activate the safety with your supporting hand. If you cannot or choose not to use your supporting hand, you can simply move your thumb to the other side of the frame, and slightly shift your grip with the lower three fingers and the thumb to maintain control of the pistol. Then, you can pull the levers down “easily” with your trigger finger and your thumb. It’s a lot easier to do than to explain. At any rate, most combat/defensive type shooting has both hands on the gun most of the time anyway, so this is not a big deal. And remember, the Steyr is safe even without having the manual safety activated, as long as the trigger is not pulled.

When the manual safety is on, you can still rack the slide to load and unload the pistol. In fact the Owner’s Manual recommends having the safety on during the loading & unloading stage.

To release the safety, you simply press “up” against the safety bar with your trigger finger, which is a distinctively different action than pulling the trigger finger backward to fire the pistol. Once you are trained with releasing the Steyr manual safety to fire mode, it’s just as “easy and fast” as toggling the more traditional manual safety with your thumb.

Out Of Battery

Firing out of battery should not be an issue with the Steyr series. It has a very strong positive lockup. As soon as the slide begins to go back, the firing pin tension is also reduced so the firing pin should not have the momentum to set off a primer.

I always check all of my spent brass before reloading. I have yet to find a primer strike that is not in the center.

My Steyr pistol passes the 12 o’clock recoil spring test with flying colors. This is a good test to check the recoil spring strength. Make sure the gun chamber is empty. Point the muzzle straight up. Pull the trigger. Keep the muzzle pointing straight up while you rack the slide and then very gently let it forward until it stops on its own accord. My Steyr pistol completely resets in the 12 o’clock position. On the other hand, my new Glocks, 22 & 23 had to be lowered to the 9 – 10 o’clock position to completely reset. Having a strong reset and lessoning slide battering is a high priority of mine.

Lubrication

Besides the directions in the owner’s manual, I’d recommend using a high Tech lubrication like Tetra or some equivalent. While regular gun oil works fine, Tetra actually penetrates the metal surface. Even if you wipe the metal dry afterwards, it’s still lubricated. Tetra is especially good to use in areas like the firing pin recess, where you want to very lightly dab a touch of Tetra, but not to the point of having oil oozing in the area; it should almost appear dry after lubing. I’ve found Tetra works well on any moving part, even plastic, such as the inside trigger mechanism.

Petroleum based lubes have a tendency to collect dirt and grime.

Lubing is one area where the Glock shines. It can work almost dry, with low-tech lube, and with high tech lube.

Accuracy

There is no other out-of-the-box, service-grade, compact pistol that will out shoot the Steyr M40. The slide to frame fit is tight, and built specifically to increase accuracy. After all, who cares what caliber you’re using if you can’t hit what you’re aiming at.

Torture testing

In June ’99, Bubits tested an early M40 “prototype” by firing 10,000 rounds through it within two days. He lubricated it once at the beginning of the session. Then he sprayed the pistol with an air hose after every 500 rounds but otherwise did not clean it thereafter. He had 5 malfunctions, one of which was a dead primer. He tweaked the extractor to fine-tune the gun for reliability.

Will the Steyr pass the torture tests of being frozen, burned, buried, dropped from helicopters, run over, etc? I don’t know. It’s a nice marketing ploy, but as long as my Steyr can handle “reasonable” torture testing, such as the flying frisbee test, etc, that’s good enough for me and any kind of shooting I’ll be doing.

I’ll be using my M40 in IPSC & IDPA shooting as well as for a defensive weapon. That means I’ll be firing it in cold, hot, dusty, & wet conditions. And I need to be able to reliably pump at least 200 – 300 rounds through it at any given match. Right now I’m feeling good that the Steyr M40 will do just fine. Once again, I really like the well supported chamber for this kind of shooting; And as a result, I feel more confident when carrying the M40 for defensive purposes as well.

I examined my M40 after shooting 1000 rounds through it during the first two weeks of ownership. There were no wear marks anywhere. The slide-to-frame fit is superbly engineered. I did find a little black paint that had rubbed off on top of the slide stop lever. This examination increases my confidence in the M40 substantially.

Steyr Service

Since the M series is new, Steyr obviously does not have an extensive armorer/repair program throughout the U.S. yet. That is changing now that Steyr has someone actively in charge of this arena. For now, you must send your pistol to GSI for repair, although their turnaround time is just a week or two.

Holsters

Steyr has selected Galco and Safariland to make holsters. Blade-Tech has ramped up to support Steyr as well. There are probably others that I’m not aware of.

Owner’s Manual

Steyr did a great job on the M Series Owner’s Manual. The manual provides all the necessary safety and pistol information, as well as some excellent pictures. There is an attachment which quotes some important Federal Laws.

Any Steyr M Series Issues?

Some of the early Steyr pistols dinged up the top of the slide a lot from ejected brass. Steyr did come out with an ecjector port tapering fix. The top, front of the ejector port edge is now tapered at about 45 degrees instead of 90 degrees. And at the top, back, right of the ejector port, it is now angled at approximately 45 degrees instead of a 90 degree corner.

I picked up a second Steyr M40 to test. There was some scoring on top of the slide, right at the rear edge by the ejection port. I doubt if most people would notice or be concerned about it.

Another Steyr customer degreased his Steyr M40 and then began having severe trigger problems. GSI told him that they would either fix it or replace it. Some people have had problems because of not cleaning and lubricating their pistols properly. A few of my Glock buddies were appalled that a pistol can actually require more than 3 1/2 drops of lubrication

I heard about one M40 that shot fantastic for about 50 rounds. Then the firing pin stopped denting the primer. The owner sent it in to GSI for repair.

One of my two M40’s did have trouble resetting at times, for no obvious reason. This problem was later fixed by using precision drilled holes in the metal sub-assembly.

In late May, 2000, I bought a 3rd M40 with a serial number in the 10,000 series. And all the above bugs have been worked out. Steyr made a few internal changes and manufacturing improvements to fine-tune the Steyr M pistols. The recoil spring seems to be slightly stronger, so the slide reset is very solid.

In late August, 2000, I sent my 10,000 series pistol to GSI for the new generation trigger upgrade. My pistol was back in three days. GSI paid the return shipping cost and gave me a $35 gift certificate. Folks, that’s excellent service.

Before the upgrade, my trigger was around 7.5 lbs or so. After the upgrade, it is 5 lbs. The really big improvement is that no matter where you place the trigger finger — high, medium, or low on the trigger — the trigger is “smooth, crisp, & consistent”!

So, the bottom line for the new Aug, 2000 trigger upgrade is, “Wow”!

I now consider the new Steyr pistols production ready and some agencies are interested in taking a look at them seriously. Steyr and GSI are ramping up training classes and law enforcement engagements, etc. Note: A lot of the early models continue to work fine, although, if you have any issues, be sure to contact GSI so they can upgrade your pistol.

Since the Steyr M (Medium) & S (Small) series pistols are new, the manufacturer could take advantage of the latest advances in ergonomics and safety. Therefore, the Steyr pistols can easily meet the most strict “common sense” State firearms safety laws.

Specifications:

Length/slide 7.05″

Height: 5.03″

Width: 1.18″

Sight radius: 6.22″

Weight: 28 oz.

Finish: Black Oxide Tenifer

Barrel length: 4.00″

Barrel rifling: RH, 6 groove

Length of twist: M40 M9 M357

15.98″ 9.85″ 16″

Trigger system: Reset Action System

Trigger pull: 5 LB’s (as of new trigger upgrade 08/00; adjustable at the factory)

Trigger travel: 1/8″

5 safeties:

3 reset action safeties: Trigger, Drop, and Firing Pin Safeties

1 Manual Safety

1 Integrated lock with two keys

1 Loaded chamber indicator

caliber M40 M9 M357

magazine capacity 10 10 10

Law Enforcement 12 14 12

Weight (without mag.) 23.87 23.17 24.45

Weight of empty mag. 2.97 2.97 2.97

Steyr M40 retail price: $669

Commercial pricing: $500 aprox. As of 10/01/00

Steyr S (Small) Series Specs:

Length/slide 6.53″

Height: 4.6″

Width: 1.18″

Weight: 22.5oz.

Barrel length: 3.58″

Magazines: 10 rounds in 9mm, .40, and 357 Sig

Chronograph Data for the Steyr M9 (from Handguns, Oct ’99)

| Group |

Size |

Velocity |

| Cor-Bon 90 gr jhp +P |

2.0 |

1515 |

| Black Hills 115 gr jhp |

2.4 |

1201 |

| Federal 115 gr jhp |

2.3 |

1147 |

| Hornady 115 gr jhp |

1.6 |

1122 |

| Remington 115 gr jhp +P |

1.8 |

1222 |

| Federal 124 gr nyclad ball |

2.3 |

1116 |

| Federal 124 gr jhp hydra-shok |

1.8 |

1103 |

| Hornady 124 gr jhp xtp |

1.6 |

1058 |

| Norma 124 gr jhp moly-coated +P |

1.2 |

1185 |

| Cor-Bon 125 gr jhp +P |

1.4 |

1226 |

*Average is the average of five five-shot groups rounded to the nearest 1/10″.

Chronograph & Accuracy Data for the Steyr M40 (from Handguns, Aug 00)

| Cartridge |

Group Size Smallest |

Group Size Largest |

*Average |

Average Velocity |

Standard Deviation |

| Cor-Bon 135 grain JHP |

2 1/4 |

4 5/8 |

3 3/8 |

1278 |

46 |

| Norma Black Diamond 155 gr JHP |

2.0 |

3.0 |

2 3/8 |

1271 |

08 |

| Hornady 155 grain XTP |

1 1/2 |

3 1/2 |

2 5/16 |

|

|

| Winchester 155 gr Silvertip HP |

2.0 |

4 3/8 |

2 3/8 |

|

|

Note: 5-shot groups fired in the Petersen Ranch Ballistic Tunnel from a Ransom Rest.

*”Average” is the average of five five-shot groups.

In Summary

The Steyr M40 is an ergonomic, well thought out pistol that’s about the same size as a Glock 19, 23, 32. All the edges of the Steyr have been rounded. It’s very comfortable to hold and shoot. Just looking at and handling a Steyr pistol in a store is not good enough. Shoot it several times and that’s what will really sell you on this pistol, along with its excellent features. I believe the Steyr has the best all-around features in a pistol today.

Regarding felt recoil, some people have claimed that the Steyr M9 (9mm version) feels more like a pellet gun than a 9mm pistol. I’m really looking forward to the M357 model as well.

Obviously, the Steyr M series is a new kid on the block and has to continue proving itself to agencies. From what I’ve seen with my own Steyr M40, this will be a moot point.

One amazing thing about the Glock design, besides its market share, is that it only has 35 listed parts, compared to 53 Steyr pistol listed parts. Although, Glock uses a few little tricks by combining some parts. I would say the Glocks really have at least 42 parts or so. Of course, the Steyr has more functionality built into it, and Steyr even lists the Pistol Box and lock keys as parts; Obviously, Steyr is not trying for a ‘Least Parts’ record :) From what I’ve seen, the Steyr M Series is made to last.

The Steyr pistols have a well supported chamber. On the other hand, as long as you use known, tested “factory” ammo in a well-maintained “Glock”, their unsupported .40S&W chamber will serve you well. But a lot of people shoot remanufactured ammo and reloads and even lead through their Glocks all the time, exacerbating this problem, not to mention bad lots of factory ammo occasionally.

Some kB (kaBoom!) information can be found at the Calibers Web site, www.greent.com/40Page. I also wrote a related article called, “You Say kB! and I say Case Failure”, located at www.glockmeister.com and www.recguns/XN.html. Another good site is John Leveron’s Glock Page at http://glock.missouri.edu/glock.shtml. And lastly, Dean Speir’s kB! Faq has some excellent pictures and is located at: http://communities.prodigy.net/sportsrec/glock-kb.html.

I personally believe that any .40 pistol with an unsupported chamber and possibly a thinner chamber wall, would most likely kB before other major pistol brands if using the same “bad factory” or “bad reloaded” ammo. And I also have a theory that the combination of polygonal rifling which seals the bullet tighter in the barrel, combined with an unsupported Glock chamber is a bad combination. But, bad ammo and bad gun maintenance aside, a Glock can hold its own very well. However, I personally prefer to use a good Bar-Sto or KKM .40 barrel in a Glock because these barrels are far kinder to the brass than a Glock barrel, and they appear to feed reliably as well — apparently Glock Inc. disagrees with me J

Since the Steyr M40 has a well supported chamber, it is safer to shoot in a wider range of shooting disciplines than a standard barreled Glock .40 S&W pistol. And the Steyr M feeds at least as reliably as a Glock, due to some great engineering.

In the Steyr Safety condition 1, with its trigger safety, drop safety, and firing pin safety, it is just as safe to carry as a Glock. The Steyr is also “easy to use” just like a Glock.

The Steyr Safety condition 2 is activated when using the manual safety. For those that want a retention safeguard of some kind, this is an important consideration. The manual safety is completely invisible if you choose not to use it, and it cannot accidentally be toggled on. The safety location is a proven design on several popular rifles and the Vector pistol, although it may at first appear strange to some traditional pistoleros.

The Steyr Safety condition 3 (integrated, limited access lock) is an excellent feature. For those with families and/or storage needs, this is an important consideration. The gun cannot be taken apart or fired when this mode is activated. The integrated lock is basically unnoticeable since it blends into the pistol so nicely.

The Steyr has a loaded chamber indicator in the back of the slide that can be seen or felt, which is really a 6th visual/tactile safety feature.

The Steyr can easily and safely shoot SWC (semi wad cutter) bullets and lead bullets — not recommended if using the polygonal rifling of a standard Glock barrel.

There are dovetails at the front and rear of the Steyr slide for the standard all-steel sights.

The large triangular front sight is excellent for fast aiming during speed shooting. And the tip of the front triangular sight helps zero you in for excellent accuracy.

The Steyr pistol has an even lower bore axis than the Glock.

The Steyr pistol has less felt recoil than a similar sized Glock 23.

The Steyr M40 has a shorter, crisper trigger pull than the standard Glock.

People with small or large hands can easily adjust to the Steyr grip.

The side of the Steyr pistol only has a simple slide lock lever and that’s it — very simple to operate.

As of June, 2000, the street price of the Steyr pistols is around $500.

When the subcompact Steyr S (small) series pistols come out in the latter half of 2000, it will be a perfect complement to the compact Steyr M series that is now available.

The slide rails are integrated into the main steel housing of the Steyr, which is a “steel pistol” that happens to be wrapped in a very strong “polymer”. This makes it a beefy design. A Glock, H&K, and Walther P99 are conversely “polymer pistols” that mold the metal slide rails directly into the “polymer”.

If I could take the liberty to compare pistols to cars, I would say that the new Steyr pistol is the “manual shift” smart gun of the 21 century, while the “automatic” electronic smart guns may or may not ever be street worthy, based on current reports.

Note: As of Oct, 2000, all Steyr pistol articles have been written based on early prototype or very early production pistols. The up-to-date pistols are taking full advantage of the fine tuned Steyr manufacturing plant and new trigger update.

I just can’t help but end my Steyr M info review with a quote from Massad Ayoob, regarding the new Steyr M Series pistols, who quoted William Shakespeare, “Something wicked cool this way comes”.

References

Guns & Weapons For Law Enforcement; “New Steyr M-Series M9mm/.40” by Wiley Clapp

Handguns; Aug 2000; “Steyr M-40 Packs A Punch” by David W Arnold

Combat Handguns; Dec ’99; “New Steyr M9/M40” by Paul Johnson.

Combat 2000 Annual; Display until April 30, 2000; “The Steyr M: Wicked Cool” by Massad Ayoob.

Guns; Oct ’99; “Steyr M9” by Massad Ayoob.

Handguns; Oct ’99; “Road Testing the new Steyr M9” by Kerby C. Smith & David W. Arnold.

Gun World; Jan 2000; “M is for Modern: Steyr’s New M-Series Pistols” by Gary Paul Johnston.

GSI INC; www.GSIfirearms.com ; Home web page of the exclusive U.S. importer of Steyr Mannlicher; 205-655-8299;

Steyr Mannlicher; www.smg.steyr.com; (+43 7252) 896 – 0

Steyr Pistol Owner’s Manual; buy a Steyr pistol to get one :)

Laser-Cast Reloading Manual, by Oregon Trail Bullet Company; 800-811-0548; www.laser-cast.com

Version 10/08/00 from Pete’s Pistol Page: http://home.earthlink.net/~petej55